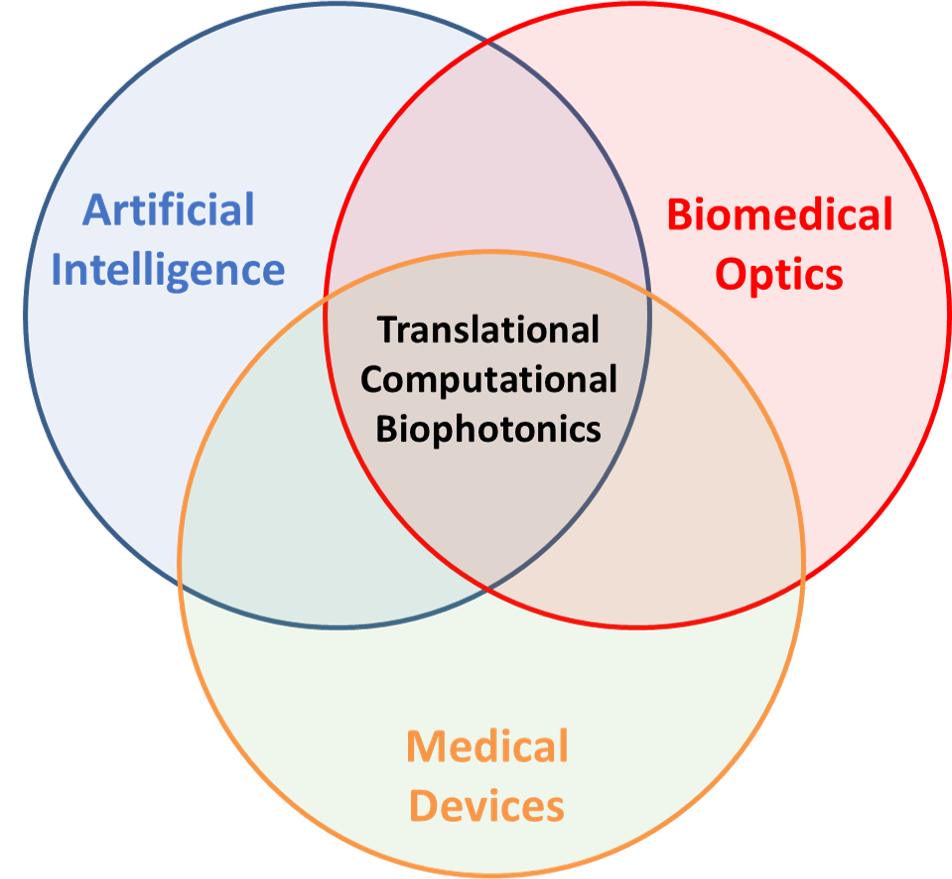

Research Overview

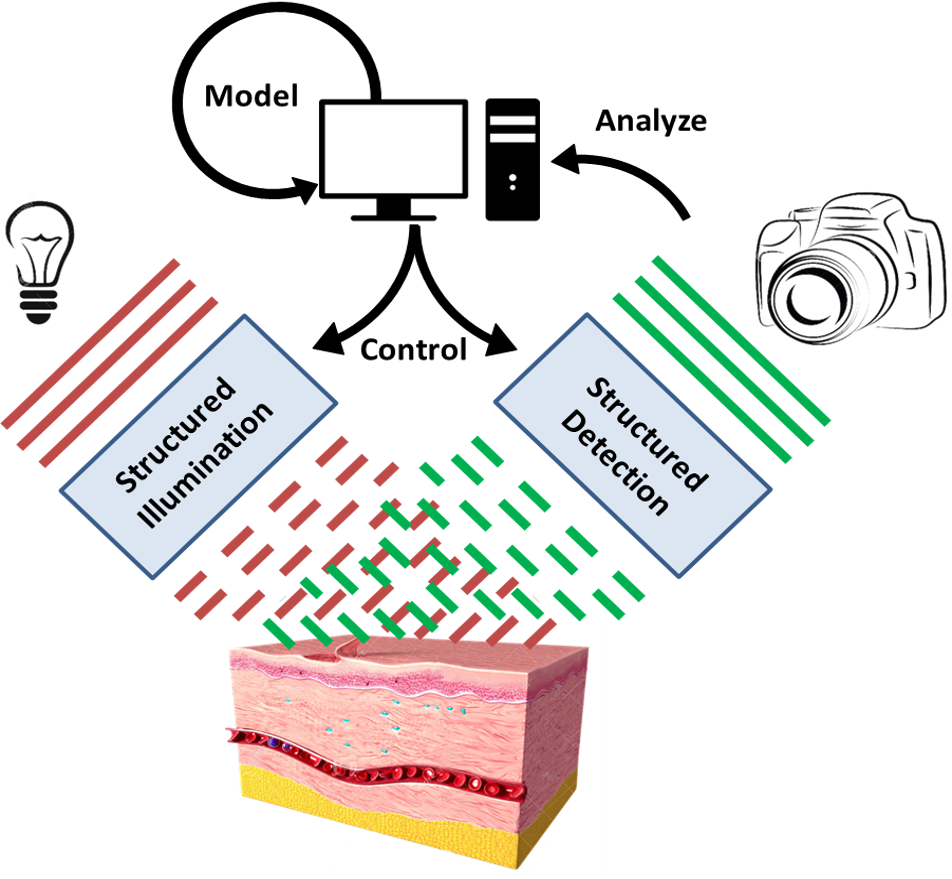

Our group creates and translates new optical technologies to elucidate important clinical information. We are particularly interested in Computational Biophotonics–creating new ways in which structured light can be used in combination with intelligent algorithms to probe and interpret the interaction of light with biological tissues.

By shaping and monitoring the spatial, temporal, spectral, and coherence properties of light as it interacts with tissues, we strive to extract physiological information that will improve diagnostics, guide treatments, monitor therapies, and lead to impactful new medical devices.

Our work is inherently interdisciplinary, incorporating concepts from: optical engineering, light-tissue interaction, computer vision, machine learning, and biodesign.

Some of our research can be framed by the following questions:

- What measurements should our imaging systems make for optimized AI analysis?

- What new “smart” medical devices might now be possible utilizing AI?

- Can deep learning work well with small training datasets and/or poor annotations?

- How can we transition from reactive diagnostics to proactive health monitoring?

- How might AI make healthcare more accessible and equitable?

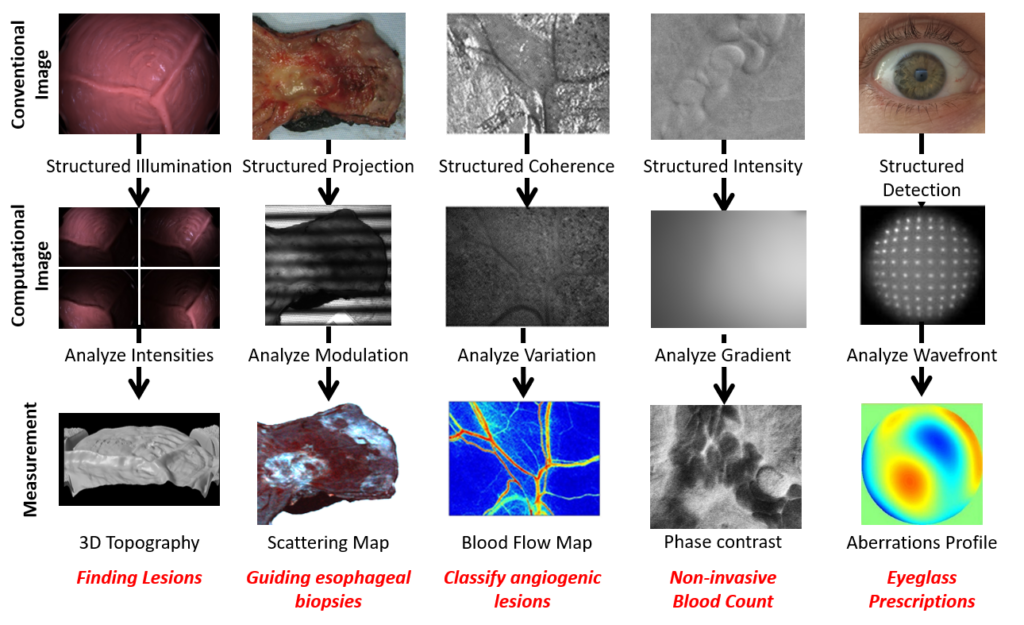

Computational Biophotonics Techniques

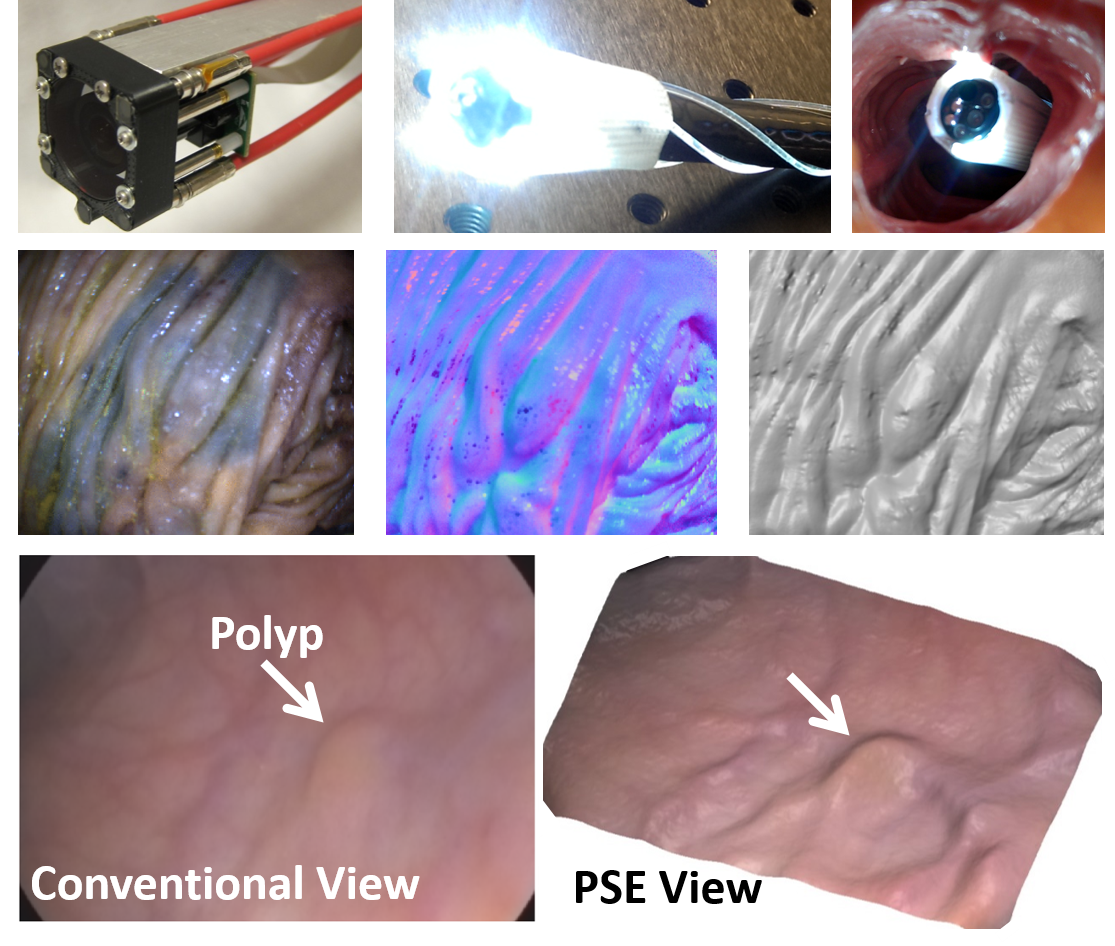

Quantitative Endoscopy

The dominant paradigm of endoscopy has remained unchanged since its inception—an endoscope provides a similar image to what the physician would see if they performed a surgery and observed the target field with their naked eye. Our group aspires to improve clinical outcomes of endoscopic procedures by developing new, quantitative, wide-field imaging techniques that reveal useful diagnostic information that is invisible to conventional endoscopes.

We’re creating new technologies to quantitatively measure the shape of the colon, such as Photometric Stereo Endoscopy (PSE). PSE can increase contrast of precancerous adenomas (“polyps”) in colonoscopy screening.

Deep Learning in Optical Imaging

Image Analysis

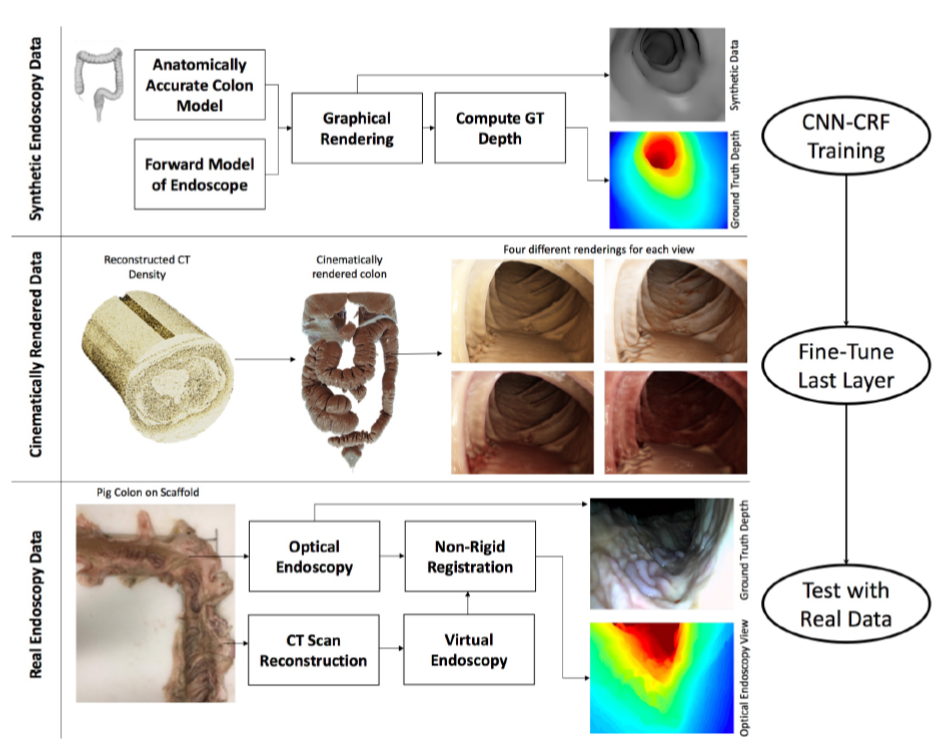

How can we train algorithms to exceed human performance? How can we harness the power of deep learning with the small, noisy datasets typically available in medical imaging? We are using synthetic data and domain adaptation to generate large training sets with error-free annotations for machine learning. This approach can enable algorithms that spot features that may be missed by a specialist and that uncover new biomarkers.

System Design

As computational tools advance, more medical images will be analyzed by computer algorithms. Conventional imaging systems are designed to optimize diagnosis by a human. We are exploring new imaging paradigms that optimize diagnosis by a computer.

Spatial Frequency Domain Imaging

Biological tissues are composed of a variety of chromophores–molecules that absorb light of characteristic wavelengths. If you measure the amount of light that a tissue absorbs, you can calculate concentrations of the chromophores present in the tissue. This is useful in many clinical applications because some of the more dominant chromophores in your tissue are markers of important clinical parameters, such as oxygenation. However, it is difficult to quantify the absorption in biological tissues because they are generally turbid. The attenuation of light in tissue is a function of both its absorption and scattering properties.

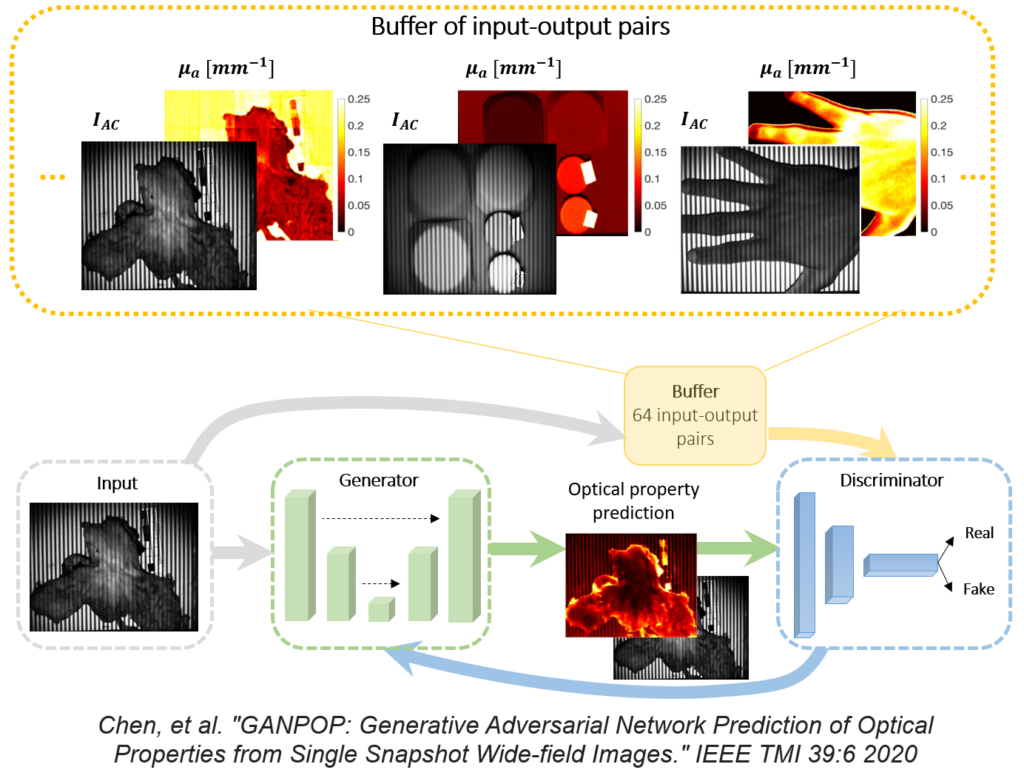

Spatial frequency domain imaging (SFDI) works by shining varying patterns of light on an object of interest. High spatial frequency patterns are attenuated primarily by scattering while low spatial frequencies patterns are attenuated primarily by absorption. SFDI exploits this phenomenon to isolate the effects of scattering and absorption create a map of tissue chromophore concentrations.

Non-invasive Blood Analysis

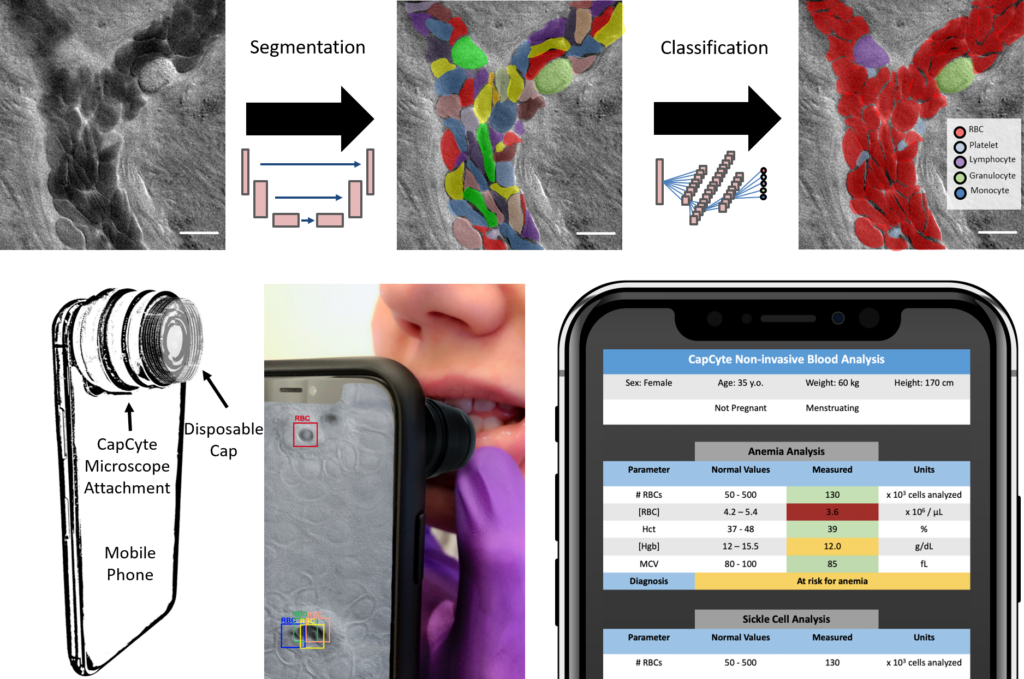

The five vital signs, which include temperature, blood pressure, pulse, breathing rate, and oxygen saturation, are critical in managing the body’s life-sustaining functions. Because these prognostic values are easy to measure and can be monitored frequently, they are used ubiquitously to manage patients. The complete blood count (CBC) is the most common blood test ordered globally, and provides similarly-critical diagnostic information for a wide variety of conditions such as infection, sepsis, hemorrhage, anemia, neutropenia, and generally identifying the need for a life-saving intervention. However, the CBC requires drawing venous blood via phlebotomy and laboratory testing, making it time-delayed, infrequent, expensive, and impractical to be utilized in the same way as the traditional vital signs. We are developing technologies for non-invasive blood analysis with the goal of making blood counts continuous, easy-to-acquire, and non-invasive.

Ocular Diagnostics

Ocular diagnostics often rely on antiquated, expensive equipment for examination. Our lab creates technologies that enable more efficient, accurate, and easy-to-use tools that will ultimately increase eye care accessibility.